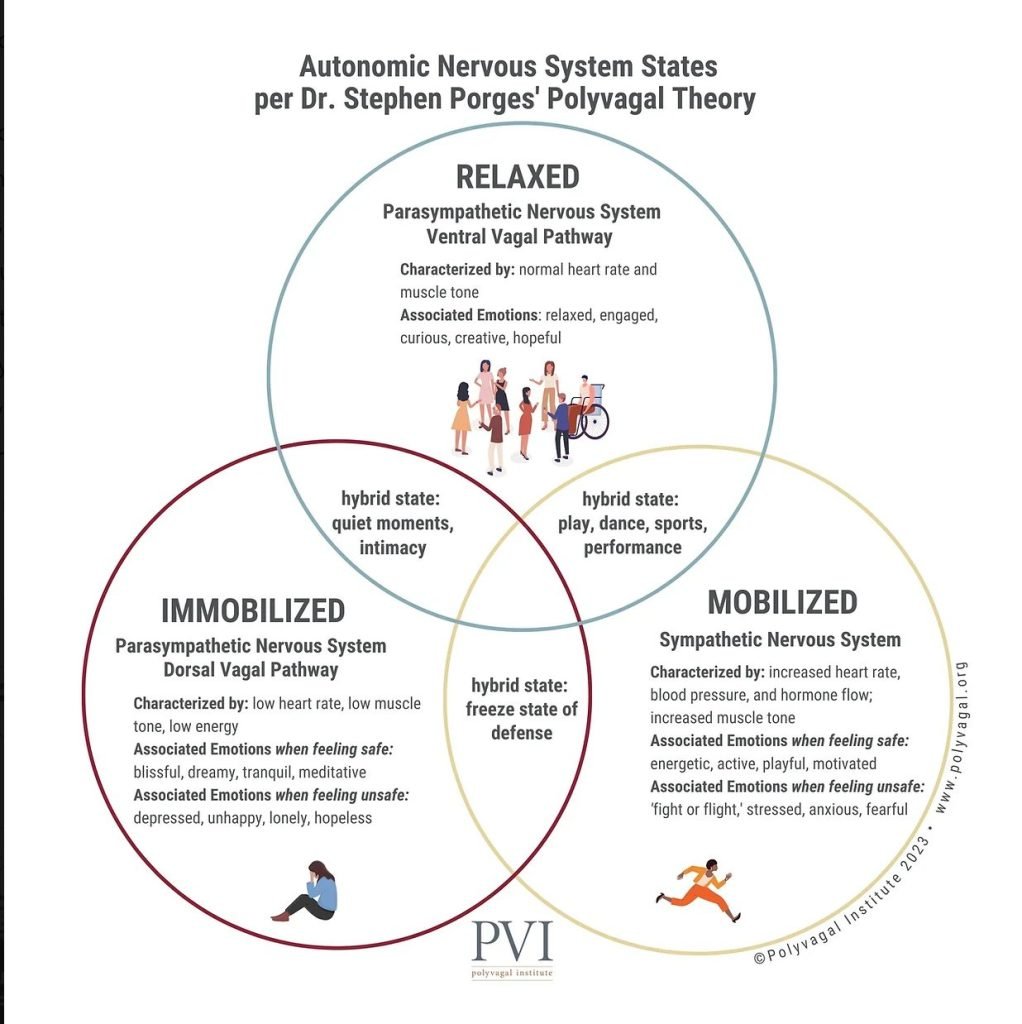

The polyvagal theory suggests that the development of the mammalian autonomic nervous system offers the neurophysiological basis for adaptive behavioural strategies. Physiological state influences the scope of behaviour and psychological experience.

Have you ever been in a situation where you feel uncertain or even in danger and you’re not sure why? You may look around and see no one else is bothered, but something still feels off.

As we go about our daily lives, we unconsciously interpret social cues like facial expressions and body language, constantly engaging with others and our surroundings. This ongoing interaction is a fundamental aspect of being human.

As we have these interactions with others, our sense of self is being shaped. We learn who we can trust and who feels dangerous to us. Our bodies are processing this type of information constantly through these interactions with the world.

The Body’s Security System

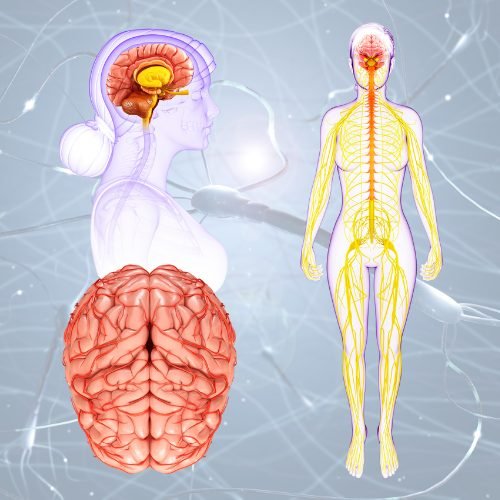

Our nervous system is a complex structure that gathers information from all over our body and coordinates activity. There are two main parts of the nervous system: the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system.

In polyvagal theory, the process in which our neural circuits read cues of danger in our environment is known as neuroception. Through this process of neuroception, we are experiencing the world in a way in which we are involuntarily scanning situations and people to determine if they are safe or dangerous.

Impact of Trauma

When someone has experienced trauma, maybe they were left immobilised, their ability to scan their environment for danger cues can become skewed. Our body’s goal is to prevent a terrifying moment like it again, so it will do whatever it needs to to protect us.

As our security system kicks into overdrive, it can also incorrectly read cues in our environment as dangerous.

When our body picks up a cue within an interaction that signals we may not be safe, it begins to respond. For most, this cue moves them into a place of a mobilisation response, springing into action to avoid or escape the threat.

A slight change of facial expression, a particular tone of voice, or certain types of body posture, may feel familiar to us and the body reacts in an effort to prepare and protect us.

In these situations, mobilisation may not be registered by the body as an option. This can be quite confusing for trauma survivors who are unaware of how this hierarchy of response is influenced by their interactions with others and the world.

The Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerve is the tenth cranial nerve, a very long and wandering nerve that begins at the medulla oblongata, a part of the brain located in the lower part of the brain just above where the brain connects with our spinal cord. Dr. Stephen Porges, Ph.D. referrs to this as The Polyvagal Theory.

There are two sides to this vagus nerve, the dorsal (back) and the ventral (front). From there, the two sides of the vagus nerve run down throughout our body. They are considered to have the widest distribution of nerves within the human body.

Both sides of our vagus nerve can be stimulated. Each side (ventral and dorsal) has been found to respond in distinct ways as we scan and process information from our environment and social interactions.

Central Nervous System

The central nervous system consists of two structures:

- Brain: This is the structure composed of billions of interconnected neurons, or nerve cells, contained in the skull. It functions as the coordinating center for almost all of our body’s functions. It is the seat of our intellect.

- Spinal cord: This is a bundled network of nerve fibers that connects most parts of our body to our brain.

Peripheral Nervous System

The peripheral nervous system consists of all of the nerves outside of our brain and spinal cord. It can be categorised into two distinct systems:

- Somatic nervous system (voluntary): This system allows our muscles and brains to communicate with each other. The somatic system helps our brain and spinal cord to send signals to our muscles to help them move, as well as sends information from the body back to the brain and spinal cord.

- Autonomic nervous system (involuntary): This is the system that controls the glands and internal organs, such as the heart, lungs, and digestive system. This system runs the important parts of our body without us having to intentionally think about them. For example, we can breathe without having to think about taking a breath each time.

How the body reacts to Danger Cues

Our autonomic nervous system is complex and always busy. In addition to running important functions in our bodies, our autonomic nervous system is also helping us to scan, interpret, and respond to danger cues.

There are two separate systems at work within our autonomic nervous system that help us read and respond to danger cues:

- Sympathetic nervous system. This system arouses our bodies to respond by mobilizing us to move when in dangerous situations. Many refer to this system as our “fight or flight” response to danger cues in our environment. It is also responsible for activating our adrenal glands to release epinephrine into our bloodstream, otherwise known as creating an adrenaline rush. When we see a snake, our sympathetic nervous system will read the cue of the potential threat and prompt our body to respond, likely involving a quick adrenaline rush and immediate movement away from the snake.

- Parasympathetic nervous system. This system is involved in calming our bodies and conserving energy by slowing our heart rate, regulating our digestion, and lowering our blood pressure. Some refer to this system as the “rest and digest” system. As we begin to read that a cue is not dangerous, our body begins to calm down with the help of our parasympathetic nervous system.

The term “fight-or-flight” represents the choices our ancient ancestors had when faced with danger in their environment: to either fight or flee. In either case, the physiological and psychological response to stress prepares the body to react to the danger.

The three stages of fight-or-flight are:

- The alarm stage: During this stage, the central nervous system is ramped up, preparing your body to fight or flee.

- The resistance stage: This is the stage in which the body attempts to normalize and recover from the initial elevated fight-or-flight response.

- The exhaustion stage: If the first two stages occur repeatedly over time, such as when under chronic stress, this can cause the body to feel exhausted and begin to break down.

This framework has evolved to encompass a broader description of reactions. These are collectively known as the 5 Fs of Trauma Response: Fight, Flight, Freeze, Fawn, and Flop.

Physical Signs of a Fight-or-Flight Response

Physical signs that can indicate that your fight-or-flight response has kicked in include:

- Dilated pupils: In times of danger, the body prepares itself to become more aware of its surroundings. Dilation of the pupils allows more light into the eyes, resulting in better vision of your surrounding area.

- Pale or flushed skin: During fight-or-flight, blood flow to the surface areas of the body is reduced while flow to the muscles, brain, legs, and arms is increased. Paleness or alternating between a pale and flushed face as blood rushes to the head and brain is common. The body’s blood clotting ability also increases to prevent excess blood loss in the event of injury.

- Rapid heart rate and breathing: Heartbeat and respiration rate increase to provide the body with the energy and oxygen needed to fuel a rapid response to danger.

- Trembling: The muscles tense and become primed for action, which can cause trembling or shaking.

The Hierarchy of responses built into our autonomic nervous system:

- Immobilization. Described as the oldest pathway, this involves an immobilization response. As you might remember, the dorsal side of the vagus nerve responds to cues of extreme danger, causing us to become immobile. This causes us to respond to fear by becoming frozen, numb, and shutting down. It is almost as if our parasympathetic nervous system is kicking into overdrive as our response causes us to freeze rather than simply slow down.

- Mobilization. Within this response, we tapped into our sympathetic nervous system which helps us mobilize in the face of a danger cue. We spring into action with our adrenaline rush to get away from danger or to fight off our threat. Polyvagal theory suggests this pathway was next to develop in the evolutionary hierarchy.

- Social engagement. The newest addition to the hierarchy of responses is based on the ventral (front) side of the vagus nerve. This part of the vagus nerve responds to feelings of safety and connection. Social engagement allows us to feel anchored, which is facilitated by that ventral vagus pathway. In this space, we can feel safe, calm, connected, and engaged.

Responses are fluid

Polyvagal theory suggests this space is fluid and we can move in and out of these different places within the hierarchy of responses easily.

As we go through life engaging with the world, there are moments when we will feel safe and others when we will feel discomfort or danger.

We can feel safe with loved ones one moment, then face danger like a car accident or a robbery the next.

There may be times when we react to a danger signal in a way that makes us feel trapped and unable to escape. During these moments, our body responds with heightened anger and distress, shifting into a primal state of immobilisation.

The dorsal vagus nerve is affected, causing us to freeze, feel numb, and potentially dissociate, according to some researchers.

Danger cues can become overwhelming in these moments and we see no viable way out. An example of this could be moments of sexual or physical abuse.

Ways to apply Polyvagal Theory to everyday life:

- Recognize your physiological response to stress: The ANS controls our bodily responses to stressors, and the different branches of the ANS are associated with different physiological responses. These responses happen even if we don’t realize that our brain has detected danger or threat. By paying attention to your bodily sensations and responses, you can recognize when your ANS is activated and what response is dominant.

- Practice self-regulation: Self-regulation is the ability to manage your emotional state and physiological responses to stressors. Many methods for self-regulation are based on activation of the vagus nerve, such as slow, diaphragmatic breathing, gentle touch, and engaging in activities that promote relaxation, such as yoga or meditation.

- Build social connections: According to Polyvagal Theory, having connection with others and exercising our social engagement system helps us regulate our emotional state. Building positive social connections can help us feel safe and secure, which can reduce stress and soothe our nervous system..

- Identify triggers: Polyvagal Theory suggests that different stimuli can trigger different branches of the ANS. By identifying your triggers, those events or situations that are threatening to you, you can better understand what situations or stimuli might activate your stress response and work to avoid or manage them.

- Seek professional support: If you are struggling with anxiety, depression, trauma, or other mental health issues, working with a mental health professional who is familiar with Polyvagal Theory can help you understand and manage your ANS responses to stressors.

Find out more from the Polyvagal Institute which is a non-profit organization founded in 2020 by Dr. Stephen Porges, Deb Dana, LCSW, Karen Onderko, and Randall Redfield, our Executive Director.